Introduction

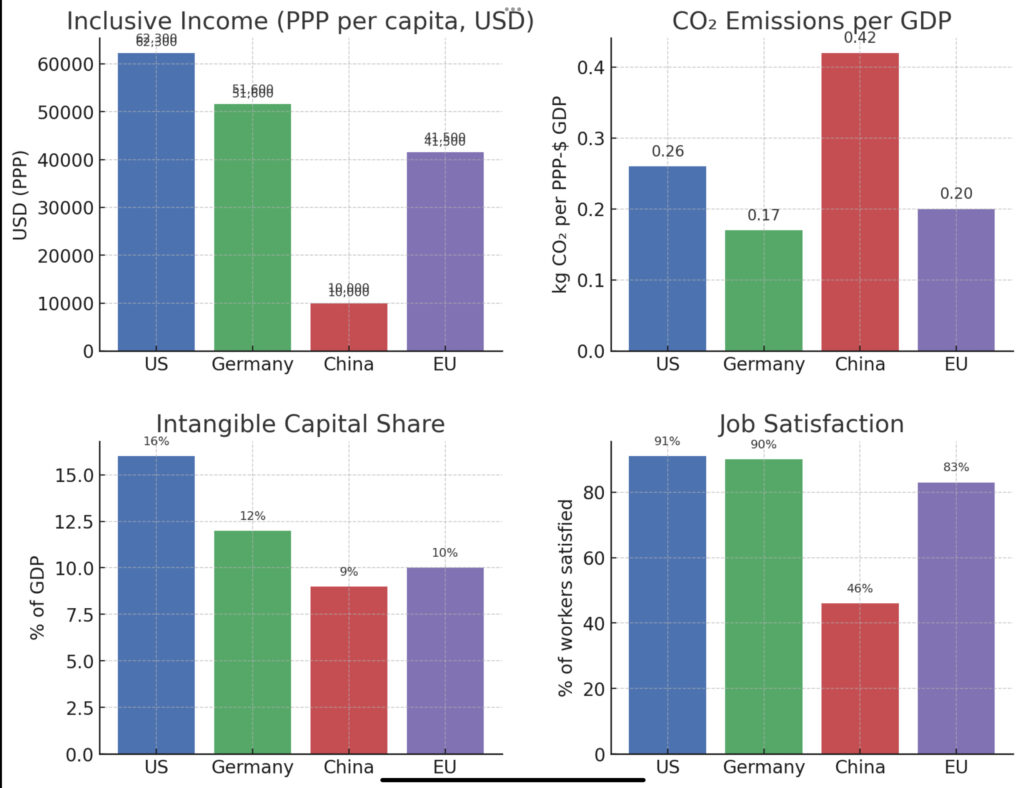

Automation and artificial intelligence are rapidly transforming the global economy, ushering in a “post‑labor” era where human work is no longer the primary driver of production. As machines and algorithms take over routine tasks, traditional metrics like GDP and unemployment alone cannot fully capture economic progress or well-being. Policymakers and business leaders must instead track new indicators that reflect inclusive prosperity, sustainability, and the changing nature of work. Key post-labor metrics include Inclusive Income (which augments GDP by accounting for non-market contributions and environmental impacts), CO₂-adjusted output (economic output evaluated alongside carbon emissions), Intangible Capital Share (the portion of economic value driven by non-physical assets like software, data, R&D and intellectual property), and the Job Quality Index (JQI) (which gauges the quality, not just quantity, of employment). These measures offer a more nuanced view of economic health in an age of automation. This article provides a comparative analysis across the United States, Germany, China, and the broader European Union, followed by strategic projections for each region and actionable recommendations for navigating the transition to a post-labor economy.

Comparative Analysis: Key Metrics in a Post‑Labor Economy

Inclusive Income and Sustainable Growth: Traditional GDP growth often overlooks unpaid work, social well-being, and environmental costs. The concept of Inclusive Income addresses this gap by adding non-monetary contributions (like household labor and volunteer work) and subtracting negative externalities (such as pollution or resource depletion) . For example, the UK’s Office for National Statistics pioneered Gross Inclusive Income (GII) and Net Inclusive Income (NII) as alternative metrics. In 2022, the UK’s GII per person grew by 2.8%, matching its rise in 2021 . Notably, NII – which further adjusts for depreciation of assets and environmental damage – increased by 5% in 2022, outpacing the country’s 4.6% GDP growth that year . This gap was driven largely by sustainability factors: the expansion of renewable energy added to inclusive growth, while a rebound in carbon emissions actually offset some of the gains – NII “might have been more” without the uptick in emissions . These figures illustrate how an economy can appear to grow robustly in GDP terms yet underperform in inclusive terms if growth comes at the cost of environmental or social well-being. Diane Coyle of Cambridge notes that GDP counts “even when [activities] destroy the environment or…mental health,” whereas inclusive measures aim to capture those wider effects . So far, the inclusive income approach has been formally adopted in the UK, but there is growing interest globally in moving “beyond GDP” to assess whether growth is sustainable and broadly shared . Other advanced economies – including those in the EU and the US – are watching these developments, and international organizations like the IMF and OECD are discussing how to compare such measures across countries . In a post-labor economy, inclusive metrics will be critical to ensure automation-driven gains actually translate into higher overall welfare, not just higher output.

CO₂-Adjusted Output and Decoupling: As automation boosts output, it becomes imperative to assess whether growth is accompanied by rising carbon emissions or achieved sustainably. CO₂-adjusted output considers economic performance in light of greenhouse gas emissions, effectively gauging “green growth.” The encouraging news is that many developed economies have decoupled economic growth from CO₂ emissions in recent decades . Germany, for instance, has increased its real GDP substantially since 1990 while cutting its greenhouse emissions roughly in half, thanks to efficiency gains and a shift to renewable energy. Across the EU, countries like France, Sweden, Denmark and Germany have managed to grow their economies while reducing annual CO₂ output . This trend accelerated in the 2010s – since about 2005, both the US and the EU have seen GDP rise even as carbon emissions fell each year . In the United States, consumption-based CO₂ emissions peaked in the mid-2000s and then declined significantly (by dozens of percentage points) through the 2010s, even as the economy kept expanding . Europe shows a similar pattern. The result is a steadily improving carbon intensity of GDP – i.e. more output per ton of CO₂ emitted – in these advanced economies. Policy efforts such as Europe’s aggressive 2030 climate targets (a 55% emissions cut from 1990 levels) and America’s clean energy investments under the Inflation Reduction Act are further aligning economic growth with decarbonization. Recent data underscore this decoupling: in 2024, energy-related CO₂ emissions in advanced economies fell by 1.1% even as their GDP grew, continuing the long-term trend of output rising without emissions growth . The European Union cut emissions by over 2% in 2024, led by a double-digit drop in coal use, while its economy managed modest growth . The United States likewise trimmed emissions by about 0.5% that year, with coal power generation hitting a 60-year low . In contrast, emerging economies still show a positive coupling – China’s emissions ticked up ~0.4% in 2024 amid economic growth , and globally emissions hit a record high of 37.8 gigatons . However, China is also rapidly pivoting to clean technologies. In 2024, China’s domestic clean energy sectors (from solar and EVs to nuclear and rail) contributed over 10% of its GDP – a milestone for green output – and these sectors accounted for fully 26% of China’s GDP growth that year . Analysts note that without the clean tech boom, China would have fallen far short of its 5% economic growth target (achieving only ~3.6%) . This indicates China is beginning to decouple growth from carbon by leveraging automation and investment in green industries, even as it remains the world’s largest CO₂ emitter for now. In a post-labor paradigm, CO₂-adjusted economic indicators will be essential: they encourage nations to pursue automation and output gains in ways that also meet climate goals, ensuring that “progress” isn’t just output at all costs but output with a shrinking carbon footprint.

Intangible Capital’s Rising Share: One hallmark of post-labor economies is the dominance of intangible capital – assets like software, data, patents, brands, and human skills – over traditional physical capital. As routine labor shrinks in importance, value creation shifts toward knowledge and intellectual property. This shift is well underway: in 2023, intangible investment accounted for over 16% of GDP in highly knowledge-intensive economies such as the United States, Sweden, and France . By comparison, a generation ago intangibles were a much smaller share – the rise of the digital economy since the 2000s has seen intangible investment growth consistently outpacing tangible investment . Continental Europe is catching up, with countries like Germany, the UK, and the Netherlands boosting their R&D, software and other intangibles; the World Intellectual Property Organization notes Germany now ranks among the top five globally for absolute intangible investment levels . The embedded chart below illustrates this trend, showing how intangible investment as a percentage of GDP has surged across advanced economies between 1995 and 2023, especially in the US and Northern Europe.

Intangible investment as a share of GDP has grown in advanced economies, surpassing tangible investment. The chart compares intangible investment (% of GDP) in 1995 (grey bars) vs 2023 (blue bars) for select countries. Sweden, the US, and France lead with ~15–17% of GDP in intangibles by 2023, followed by the UK, Netherlands, and others. Source: WIPO Global Intangible Investment Database .

The United States stands out as the most “intangible-rich” major economy, with its tech giants and highly valued brands – a recent analysis found U.S. firms lead the world in utilization of intangible assets across every sector, from tech and finance to manufacturing . Germany and other Northern European countries also have high intangible intensity, reflecting strong industrial R&D, engineering know-how, and organizational capital . In contrast, China’s economy, while huge, remains less intangible-intensive. Emerging markets like China, Brazil, and India have tended to rely more on tangible investments (factories, infrastructure) and still have a lower share of GDP in intangibles . China is investing heavily to change this – for example, it produces massive numbers of STEM graduates and has national strategies to boost R&D and domestic high-tech firms – but challenges remain in translating intangible spending into productivity. Evidence suggests that China has yet to reap commensurate gains from its intangible investments: one study noted that, unlike in the US and Germany, rising intangible capital in China has not yielded proportional increases in output per capita . Inefficiencies, lagging managerial know-how, and reliance on state-driven projects mean China’s intangible capital (e.g. in software or design) doesn’t boost growth as much as in advanced Western economies . Nonetheless, the trend is clear globally – as labor’s share of value-added declines, the capital share rises, especially the share attributable to intangibles. (In fact, the labor share of national income in advanced economies fell from ~54% in 1980 to about 50.5% by the mid-2010s , a shift closely tied to the rise of capital-intensive and IP-intensive industries.) For policymakers, this means future growth will depend on nurturing intangible assets – education, research, innovation ecosystems – rather than sheer labor or heavy machinery. It also poses distributional questions: returns to intangibles often accrue to a few patent owners or superstar firms, contributing to inequality if not broadly shared . Monitoring the intangible capital share alongside inclusive income thus becomes important to ensure the wealth generated by the knowledge economy benefits society at large.

Job Quality Index and the Changing Nature of Work: In a post-labor economy, the quantity of jobs is not the only concern – the quality of remaining jobs becomes paramount. Automation may eliminate many routine, low-skill jobs but also create new roles that are often higher-skill; at the same time, there’s a risk that the jobs that remain for humans polarize into “good” high-paying jobs and “bad” low-paying, precarious jobs. The Job Quality Index (JQI) is one tool to track this balance. It typically measures the ratio of desirable jobs (with higher wages, benefits, security, and satisfaction) to lower-quality jobs in an economy. In the United States, the private sector JQI has persistently scored below 100 in recent years (e.g. around 82–84 in 2024) – a reading below 100 signifies a greater prevalence of lower-wage or lower-hour jobs compared to high-wage jobs . In fact, U.S. labor market growth for decades has skewed toward low-quality positions: “for over 30 years the U.S. economy has created more low-quality jobs than high-quality” overall . This reflects trends like the decline of middle-class manufacturing work and the rise of lower-paid service jobs, gig work, and other less secure employment. Europe, by contrast, has placed more policy emphasis on job quality – through stronger labor protections, collective bargaining, and social safety nets – and generally sees a more equal distribution of job quality. European indices of job quality (such as the EU’s JQI developed by the European Trade Union Institute) incorporate dimensions like fair wages, working conditions, and work-life balance; Northern European countries often score higher on such measures compared to the US. That said, Europe is not immune to job polarization (there are concerns over temporary contracts and gig-economy expansion in parts of Europe too). Germany, for example, has a strong base of high-skill manufacturing and engineering jobs – which are generally well-paid and stable – but also a service sector with many low-wage mini-jobs. China, meanwhile, faces a dual challenge on job quality. On one hand, rapid industrialization and urbanization have lifted millions into better-paying manufacturing and service jobs; on the other, a large share of workers (especially rural migrants and gig workers in delivery or ride-hailing) still work long hours for relatively low wages and limited benefits. As automation progresses, some low-skill roles will vanish, putting pressure on China to create higher-quality urban jobs to absorb displaced workers. Ensuring social protections for informal and platform-economy workers is already rising on China’s policy agenda. In all regions, the JQI and similar indicators push leaders to ask: are we creating “good jobs” in the new economy or just menial gigs? High job quality has broad benefits – it improves productivity, innovation, and social cohesion while reducing inequality . Thus, a post-labor strategy must prioritize not only technological efficiency but also the human dimension of work: empowering workers with skills, fair pay, security, and opportunities for meaningful contribution.

Strategic Projections by Region

United States

The United States is poised to remain at the forefront of the post-labor transition, albeit with significant challenges to manage. Automation adoption is expected to accelerate in the late 2020s, from self-driving vehicles to AI-driven professional services. This will boost productivity and output, further increasing the share of GDP derived from capital (especially intangible capital like software and AI algorithms). U.S. companies, which already lead in intangible asset utilization, will likely deepen this advantage – in all industries, American firms have been quicker than international peers to incorporate advanced technologies and intangible-driven business models . By 2030, intangibles could account for an even larger slice of U.S. investment (potentially well above 20% of GDP), reinforcing the country’s innovation-driven growth. The flip side is a continued decline in labor’s share of income if policy doesn’t intervene; the trend of the past few decades (U.S. labor share dropping over 6 percentage points since 2000 ) may continue as automation and “superstar” firms concentrate wealth . In terms of employment, the U.S. will likely create many new jobs in tech, healthcare, and green energy, but may eliminate millions of routine jobs. Estimates suggest the U.S. could lose over 1.5 million jobs to automation by 2030 just in manufacturing and see large occupational shifts in sectors like food service and retail . The net outcome could be labor shortages in high-skill fields and labor surpluses in low-skill labor, putting a premium on retraining and education. On current trajectory, job quality polarization might intensify: without policy action, the bulk of new jobs could be either very high-skill or very low-wage, with the middle hollowed out. This calls for strategic interventions to improve job quality – for instance, raising minimum wages, expanding benefits to gig workers, and incentivizing the creation of mid-skill roles (perhaps via infrastructure projects or advanced manufacturing). CO₂-adjusted growth in the U.S. should remain positive; the country’s emissions are on a downward trend (aided by the shift from coal to gas and renewables), and federal climate investments are targeting a 50% emissions cut by 2030. The U.S. likely won’t decouple as fast as the EU (due to higher baseline emissions and political swings), but it is projected to steadily lower emissions while growing – effectively meaning its “CO₂-adjusted GDP” (GDP minus the social cost of carbon) will improve. By 2030, the U.S. aims for an electricity sector that is 80% clean, heralding a significant reduction in CO₂ per unit of output. Overall, if managed wisely, the U.S. can harness automation to drive strong output and income growth, but it will need robust policies to ensure the gains are inclusive – preventing a post-labor scenario of a wealthy tech elite and a stressed precariat. Debates around universal basic income or job guarantees may gain traction as potential solutions if job displacement becomes severe.

Germany

Germany enters the post-labor era with a mix of strengths and vulnerabilities. As Europe’s manufacturing powerhouse, Germany has been a pioneer in adopting robotics and Industry 4.0 automation on factory floors. It has one of the highest robot densities in the world (over 300 industrial robots per 10,000 employees in manufacturing, ranking third globally) . Going forward, German industry is expected to automate further, especially to cope with an aging workforce and to reshore some production competitively. This suggests Germany’s labor productivity will continue to rise, and its reliance on human manual labor will decline in sectors like automotive, machinery, and chemicals. However, Germany also faces a demographic crunch – a shrinking working-age population – which means automation is as much necessity as opportunity. Fewer workers will be available, so automating tasks is critical to sustain output. By the early 2030s, Germany’s workforce could be several million workers smaller than today, absent immigration , which implies that many “missing” workers will be replaced by machines or AI. On the economic metrics front, expect intangible capital to grow in importance for Germany too, though with a distinctive German flavor: heavy investment in R&D and engineering (Germany already invests 3%+ of GDP in R&D) will drive its intangible growth, along with organizational capital in its renowned Mittelstand companies. The country has lagged the U.S. in some digital sectors, but initiatives are in place to boost digital infrastructure and AI development. By 2025–2030, Germany’s intangible investment share should inch closer to U.S. levels (perhaps into the low teens percent of GDP, up from ~10% in 2023). Job quality in Germany is likely to remain relatively high on average – strong unions and co-determination practices mean workers have a say in managing technological change (for example, negotiating reduced working hours or retraining when automation is introduced, rather than mass layoffs). Indeed, one projection of a post-labor future in Germany is a shorter standard workweek (some unions have even floated 4-day workweek trials as productivity rises). Nonetheless, there is a risk of a two-tier labor market: high-skill engineers and professionals will thrive, while some lower-skill service workers (e.g. in logistics, care, hospitality) could face stagnant wages or replacement by AI (such as autonomous vehicles threatening truck-driving jobs). Policymakers will likely double down on education and apprenticeships to up-skill workers into the higher-value roles that automation creates. Germany and the EU also strongly emphasize green transitions – Germany aims for carbon neutrality by 2045 and is investing in electric mobility, green hydrogen, and renewable power. Its CO₂-adjusted output is projected to improve markedly as coal is phased out (by 2030 for power generation) and heavy industry adopts clean technologies. By embracing both automation and decarbonization, Germany is charting a path for a high-tech, climate-friendly economy with a high standard of living. The challenge will be ensuring its many small and medium-sized firms can also adapt – not just the big Siemens and Volkswagens – so that the benefits of the post-labor economy are broad-based across regions and communities.

China

China faces perhaps the most dramatic post-labor transformation, due to the sheer scale of its workforce and the speed of its technological adoption. On the one hand, China is aggressively pursuing automation and AI as a national strategy – from factories staffed by robots to AI-driven services – in order to climb the value chain and counteract rising labor costs. President Xi Jinping’s calls for a “robot revolution” and programs like Made in China 2025 signal the government’s intent to automate widely . Indeed, China has become the world’s largest market for industrial robots, purchasing tens of thousands of units annually, and aims to automate sectors like electronics, automotive, and even fast food. By some estimates, up to 100 million Chinese workers may need to change occupations by 2030 if automation is adopted at a rapid pace – an enormous labor transition. This includes roles in manufacturing, but also clerical and service jobs susceptible to AI. Such displacement presents a risk of unemployment or social unrest if new opportunities do not emerge quickly enough. However, history suggests China will also create new jobs in tech, entrepreneurship, and the green economy. In fact, China is banking on high-tech industries (semiconductors, electric vehicles, biotechnology, etc.) to provide the next wave of employment. The government is heavily investing in human capital – producing millions of STEM graduates and building research parks – to support this pivot . Over the coming decade, we can expect intangible capital’s role in China to grow: more of China’s growth will come from innovation and intellectual property developed domestically, rather than just labor and capital accumulation. China’s R&D spending is already second only to the U.S. and rising. If China can improve the efficiency of this innovation (turning patents into profitable products and services), its intangible capital share of output will surge, helping offset labor force decline. At the same time, job quality is a significant concern. Much of China’s workforce is still in relatively low-wage activities (including informal work). Automation could worsen inequality by wiping out certain low-skill jobs while enriching tech-savvy workers and firm owners. The government is aware of this and has begun to extend basic social protections to gig workers and rural migrants. By 2025, expect more reforms aimed at labor rights in the platform economy (e.g. setting guidelines for food delivery driver pay and safety) and initiatives to transition laid-off industrial workers into service or tech jobs (perhaps through government-funded retraining programs). Environmental sustainability will be another defining factor: China has pledged to peak CO₂ emissions by 2030 and reach carbon neutrality by 2060. Achieving these goals requires a massive restructuring of its energy and industrial systems – effectively a decoupling of growth from fossil fuels. The encouraging news, as noted, is that China’s booming clean tech sector is already bolstering growth . In the next decade, we will likely see China dominate in renewable energy capacity, electric vehicle production, and other green technologies. This means China’s CO₂-adjusted economic performance should improve: GDP growth will increasingly come from low-carbon sectors. If coal and oil use plateau and renewables continue their exponential rise, China could flatten its emissions curve even as it grows, bending toward a more sustainable trajectory. In summary, China’s post-labor economy will be characterized by rapid automation, a push for indigenous innovation, and a balancing act between growth and social stability. How China manages the potential displacement of tens of millions of workers – whether through new job creation, expanding the service sector, or perhaps shortening working hours – will have enormous implications for its social contract.

European Union

The European Union as a whole provides a nuanced picture, as it encompasses advanced economies like Germany and France as well as smaller or emerging members in Eastern Europe. Overall, the EU’s strategy for the post-labor future is anchored in its concept of a “Just Transition.” Policymakers in Brussels and member states are proactively trying to anticipate automation’s impacts and ensure that no region or demographic group is left behind. Automation levels in Europe will vary – highly industrial nations (Germany, Italy) and tech-focused ones (Nordics, Estonia) will adopt AI and robotics quickly, whereas lower-wage Eastern European countries may see a slower uptake (because cheaper labor can delay the automation incentive). Still, by 2030 the EU is expected to have automated a substantial share of production in sectors like manufacturing, agriculture (with agri-robots and drones), and even public services (via digital government and AI). Labor shortages due to aging are even more acute in Europe than the U.S., making automation critical to maintain growth. For instance, countries like Poland and Spain face steep declines in working-age population by 2030, pushing them to use automation in everything from factories to eldercare. The EU will likely expand programs for cross-border retraining and mobility so that workers from shrinking industries (say, auto assembly if heavily automated) can transition to growing ones (like renewable energy installation or IT services). Intangible capital in Europe is set to grow as well – the EU has launched initiatives to spur digital innovation, AI research, and the commercialization of European technologies (recognizing they lag behind U.S. and Chinese tech giants in some areas). By the late 2020s, expect Europe’s knowledge economy to be much stronger, aided by its solid education systems and new funding mechanisms (e.g. EU-wide research grants for AI and green tech). Leading countries like France, the Netherlands, and Finland already invest heavily in intangibles; others are catching up. The EU average intangible investment share (around 7–10% of GDP now in many countries) will climb closer to U.S. levels, but the bloc will also emphasize public intangible investments – such as digital skills training and open research – not just private R&D. Job quality is where Europe hopes to distinguish itself in the post-labor era. European labor models, with stronger safety nets, may cushion workers through automation shocks better than elsewhere. We may see broader use of work-sharing: instead of one worker being laid off while another works 40 hours, two workers might each work 20 hours with partial wage support, for example. Some European countries already subsidize reduced working hours to avoid layoffs during downturns; similar thinking could apply during the tech transition. The EU is also encouraging continuous learning (the “Skills Agenda for Europe”) so that workers routinely update their competencies over their careers. By 2030, one can envision an EU workforce that is smaller but more highly skilled, with many people shifting roles multiple times (e.g. a former factory worker retrained as a wind turbine technician). The green economy is a massive source of new high-quality jobs in Europe – the EU’s Green Deal investments are creating jobs in renewable energy, building retrofitting, and environmental management. These jobs often pay well and are geographically spread (wind farms in rural areas, etc.), which helps regional equity. In terms of CO₂-adjusted output, Europe is likely to remain a world leader. It is on track to significantly cut emissions (the EU already cut greenhouse emissions ~30% from 1990 to 2020, and is aiming for 55% by 2030). As a result, EU’s economic growth is increasingly climate-neutral – essentially, Europe’s net economic welfare (when deducting carbon damage) will rise faster than its GDP. A potential risk is energy security and costs during the transition (as seen in recent years, if not managed well, high energy prices could cause public backlash), but the long-term trajectory is a decarbonized, automated economy. In essence, the EU in 2030 will strive to be a model of “high-tech, high-humanity” capitalism – leveraging robots and AI, but also valuing worker rights, equity, and environmental stewardship in equal measure.

Policy and Business Recommendations

For policymakers and business leaders charting a course through these transitions, several actionable strategies emerge from the above analysis:

- Adopt and Track Beyond-GDP Metrics: Governments should officially incorporate metrics like Inclusive Income, CO₂-adjusted output, and Job Quality Index into their reporting and decision-making. These indicators will provide early warning signs if, for example, output gains are coming at the expense of societal well-being or if job quality is deteriorating. As seen in the UK pilot, inclusive measures can diverge from GDP – highlighting sustainability issues that need policy response . International bodies (IMF, OECD) can help standardize these metrics . Businesses, too, can use these metrics internally: for instance, firms can report an adjusted profit that accounts for their carbon footprint cost, or track the quality of jobs they offer (wages, training hours, etc.) as a key performance indicator. What gets measured gets managed – by broadening metrics, leaders can better manage a post-labor economy for long-run prosperity.

- Invest in Intangible Capital and Human Capital: As the engine of value creation shifts to intangibles, countries must invest aggressively in R&D, education, digital infrastructure, and training. This means not only incentivizing private-sector innovation but also funding public research and ensuring strong intellectual property systems. Policies could include R&D tax credits, support for startup ecosystems, and university-industry partnerships to commercialize research. On the workforce side, a massive upskilling and reskilling effort is crucial. Governments should implement lifelong learning programs and vocational training focused on skills for the future (AI, data analysis, green tech maintenance, creative industries, etc.). Companies should likewise invest in their workers’ skills, viewing it as building their human capital asset. Germany’s dual education system and China’s ramp-up of STEM graduates exemplify paths to strengthening human capital for an automated era . With the right skills, workers displaced by automation can move into new roles rather than permanent unemployment.

- Enhance Job Quality through Labor Market Innovations: Policymakers should proactively manage the job quality implications of automation. This can include raising minimum standards (e.g. phased increases in minimum wage to ensure full-time workers earn a living wage even in lower-tier jobs) and extending benefits and protections to non-traditional workers (gig economy contractors, part-time workers, etc.). Portable benefits models or universal basic benefits funded through new mechanisms might be considered so that even if people change jobs frequently or work in flexible arrangements, they don’t lose healthcare, retirement contributions, or other safety nets. Governments and industry could collaborate on job redesign initiatives – examining how to make emerging jobs more enriching and secure. For instance, as routine tasks are automated, the remaining tasks for humans could be crafted to be more creative and less menial. Europe’s approach of collective bargaining and social dialogue can guide solutions, ensuring workers have a voice in shaping fair conditions in the AI era . Business leaders should recognize that improving job quality (through better pay, upskilling opportunities, and worker engagement) is not just a social goal but also boosts productivity and retention. A well-trained, fairly compensated workforce is better able to work alongside advanced technologies effectively. In short, design the future workplace with “augmented workers” in mind – humans empowered by technology, not competing with it on unequal terms.

- Leverage Automation for Inclusive Growth, Not Just Cost-Cutting: Both policy and corporate strategy should pivot from viewing automation purely as a cost-reduction tool to seeing it as a means for expanding capabilities and generating inclusive growth. This involves identifying sectors where automation can create new services and markets (for example, eldercare robotics to assist aging populations, which can improve quality of life and create new businesses) rather than solely focusing on sectors where robots can replace workers to save money. Governments can offer incentives for automation projects that demonstrably create complementary jobs (e.g. a smart infrastructure project that employs people in installation and maintenance of AI systems) or that occur in tandem with employee profit-sharing and reduced work hours instead of layoffs. One idea is tax reform: some economists have floated taxing excessive use of automation or giving tax breaks for companies that retrain or redeploy workers instead of firing them when automating. While difficult to implement, the principle is to align the profit motive with employment objectives. Policymakers might also expand public sector employment in areas like education, healthcare, and green initiatives – absorbing workers displaced from the private sector by automation into socially valuable roles that are hard to automate (teaching, caregiving, climate adaptation projects). This ensures that productivity gains translate into broader societal gains (better services) and maintain aggregate demand by keeping people employed.

- Integrate Climate Action with Economic Strategy: To achieve strong CO₂-adjusted growth, leaders must make decarbonization a core element of their economic plans, not a side effort. This means scaling up investment in renewable energy, energy efficiency, and clean technologies, which has dual benefits: it creates jobs (often good jobs) and reduces emissions per unit of GDP. The example of China deriving a quarter of its growth from clean tech in 2024 is instructive – all regions can seek opportunities in the green economy. Policies such as carbon pricing (to make polluting activities relatively less attractive economically) and green subsidies (to accelerate clean tech adoption) will help decouple growth from emissions. Businesses should similarly pursue “net-zero” strategies, improving their energy efficiency and innovating low-carbon products to stay ahead in a market that will increasingly favor sustainable solutions. Automation itself can aid climate goals (e.g. smart grids, AI-optimized logistics reducing fuel use). By tying economic recovery programs or innovation funds to low-carbon criteria, policymakers ensure that as the labor-intensive past gives way to an automated future, that future is also climate-resilient. In essence, the post-labor economy must also be the low-carbon economy – achieving productivity without pollution.

- Prepare for Social Transitions with Safety Nets and New Institutions: Even with the best foresight, the transition to a post-labor economy will disrupt lives. Policymakers should strengthen social safety nets now. This includes unemployment insurance modernization (perhaps adapting it into “income insurance” for those between gigs or learning new skills), considering concepts like Universal Basic Income (UBI) or guaranteed minimum income floors as backstops if technological unemployment surges, and ensuring access to affordable education and healthcare irrespective of employment status. Pilot programs for UBI in some regions, or negative income tax models, can be expanded if evidence shows they help maintain social stability during job transitions. Additionally, new institutional thinking might be needed – for example, creating a “Civilian Tech Corps” where displaced workers can enlist to work on public-interest tech projects (digitizing government services, local automation needs for small businesses, etc.), thereby both employing people and spreading tech benefits to all corners of society. Public-private partnerships will be key: governments can’t do it alone, and businesses have a role in funding re-skilling or participating in apprenticeships at scale. By planning these supports proactively, leaders can prevent the worst-case scenarios of the post-labor shift – mass unemployment, unrest, and greater inequality – and instead steer toward a future where economic abundance from automation is shared and enjoyed by all.

Conclusion

The dawn of the post-labor economy carries both great promise and great responsibility for today’s policymakers and business strategists. The promise lies in a world where intelligent machines unlock productivity and humans are freed from drudgery, where growth is sustainable and knowledge-powered, and where people’s basic needs can be met with less toil. The responsibility lies in guiding this transition such that it enhances human well-being rather than undermining it. The United States, Germany, China, and the European Union – each in their own way – are bellwethers in this journey. By rigorously tracking new metrics of progress and proactively shaping policy around them, these economies can navigate the complex shifts in labor, capital, and environment that are underway. The Inclusive Income of nations must rise, not just their GDP. Economic output must increase even as CO₂ emissions decrease, proving that growth and green goals can align. Intangible capital must be cultivated widely, so innovation becomes a tide that lifts all boats, not just a select few. And the quality of jobs and livelihoods must remain at the center, reminding us that economies ultimately serve people, not the other way around.

The next decade will be critical. Decisions made now – on education, infrastructure, social policy, climate action, and technological governance – will determine whether the post-labor future is one of broad-based prosperity or stark divides. By learning from each other’s experiences and remaining adaptable, the U.S., Europe, and China can each craft models of a post-labor society that suit their values and circumstances while sharing the common threads of analytical foresight, inclusivity, and sustainability. The future of work and wealth need not be a zero-sum game between humans and machines. With enlightened leadership, we can harness automation to unlock human potential on a greater scale than ever before – ushering in not an era without work, but an era with higher forms of work and a more equitable distribution of the fruits of progress. Such is the future of post-labor economies that we must strive to build, starting now.

Sources: Recent analyses and data from ONS (UK) on Inclusive Income , Our World in Data and IEA on emissions and decoupling , WIPO and Sparkline Capital on intangible investment trends , World Bank and CPA research on job quality , and various expert projections have informed these insights. Each region’s snapshot draws on current metrics (2024–2025) and stated policy targets to project likely trajectories. By heeding this evidence, decision-makers can better prepare for the profound economic transition on the horizon.